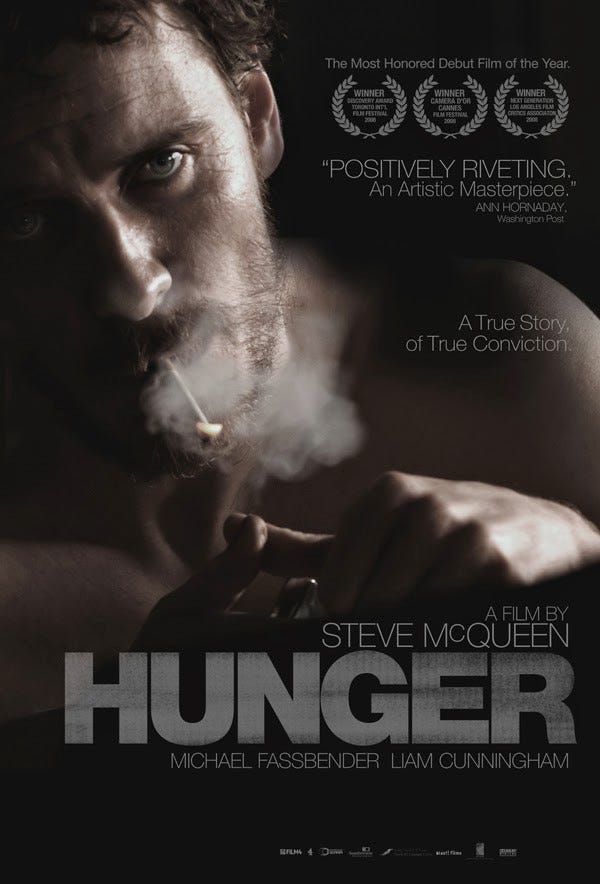

Steve McQueen’s astonishing debut film.

The best Michael Fassbender/Steve McQueen film until the next Michael Fassbender/Steve McQueen film three years later in the guise of the masterful Shame in 2011. Shame is Steve McQueen’s greatest achievement in film to date, far ahead of his 2013 Oscar winner and just a tick in front of his debut here from fifteen years ago.

I’m planning on re-releasing my original rambling musings on McQueen’s incredible Shame in the near future, but should you wish to skip the waiting queue I’ve linked my original longer blog article on the London born filmmaker immediately below (my ramblings on 12 Years a Slave included) or please skip a little further for my original review of his remarkable debut film.

Steve McQueen — Hunger, Shame & 12 Years a Slave

Originally published on 17th September 2014 and a trio of gems I had to re-watch and tidy up my original appreciation.medium.com

“2,187 people have been killed in ‘The Troubles’ since 1969”

“The British Government has withdrawn the political status of all paramilitary prisoners”

“Irish Republicans in the Maze Prison are on a ‘Blanket’ and ‘No Wash’ protest”

Six years have passed since I watched this harrowing, difficult to watch and difficult to comprehend first film from Steve McQueen and several re-watching’s of his debut film later still leave me heartbroken and in utter dismay as the closing credits roll. To say this is a tough film to watch is an understatement and it’s similarly not a film for everyone, regardless of where you stand on the political spectrum. It’s mournful, acutely distressing, disturbing and regardless of how many times I’ve watched this film the grim reality of the real life events it depicts puts me on edge every single time. It’s the mark of a fantastic cinematic experience and the mark of a feature debut film that should be regarded as a modern classic, and one that remains a harrowing watch time after time. That the events the film depicts happened just 33 short years ago remains a stain on the British consciousness and along with Bloody Sunday, another deeply depressing low in the Northern Ireland “troubles” as they were constantly referred as. For what’s it’s worth, I’m politically homeless and have been since 1997 and not a student of history but I consider myself a well read and well informed human being. It strikes me every time I watch this melancholic masterpiece that if prisoners are treated so inhumanely and have to resort to wearing just a blanket, living in their own filthy excrement and beaten savagely to near the point of death for doing so, maybe the system they’re living under doesn’t work any more?

Thankfully times have changed, however it could be argued that this film shines a light on today’s treatment of political prisoners too. The violent, bloody and brutal treatment depicted here have been replaced by psychological torture, of rendition, water boarding and constant interrogation, and of 24 hours a day strobe lighting, orange jumpsuits and Barney the Dinosaur rendering the prisoners unable to think or act straight. Is either method a success? Is either method humane to our fellow man? Is this the sum total of our efforts after millions of years of evolution? Steve McQueen’s astonishing debut film shines a light on all this and so much more.

Supported by Film 4, Channel 4, Northern Ireland Screen and Broadcast Commission and the Wales Creative IP Fund, the screenplay was also written by first time Director McQueen and Enda Walsh. The film depicts the grotesque and grim reality of life inside Northern Ireland’s notorious and infamous Maze Prison in 1981 which housed Irish Republican Army (IRA) prisoners who, without recognition of political status and under the orders of their leadership are on a “blanket” and “no wash” protest. This is starkly shown in two of the film’s earliest scenes as “Davey Gillen” (Brian Milligan) enters an excrement ridden cell and as the camera slowly pans around the small cell it is entirely covered in faeces from his fellow cell inmate “Gerry Campbell” (Liam McMahon). The second scene starkly depicts the prison authorities response to the no wash protest as they drag a kicking and screaming “Bobby Sands” (Michael Fassbender) through the prison corridors and into the bathroom, savagely beating him as they do so. They forcibly remove his hair and beard before unceremoniously dumping him into a bathtub and scrub him vigorously with a yard brush. Both these scenes are grimly realised and particularly difficult to watch.

The film has a sum total of just nineteen main characters and the Prison Authorities are portrayed through the eyes and actions of two characters, one a frightened young riot police officer crying uncontrollably behind a wall during a particularly savage beating but it’s “Raymond Lohan” (Stuart Graham) who takes centre stage and it’s through him that we see the film’s obvious juxtapositions that permeate the film. Against the backdrop of bloodied and bruised naked prisoners he is, on the surface at least, calm and methodical as he enjoys a pleasant breakfast at home and dressing immaculately in his pristine prison uniform. But he too is tortured by the brutal beatings and the insanity that surrounds him at his place of work and ever watchful as he checks under his car for any attached bombs that may have been placed there. It is a still and almost wordless performance of poise and reflection from Graham and perfectly encapsulated as he washes the blood from his bruised knuckles, the blood from the prisoner he has just beaten. Whilst their respective lives couldn’t be any more different or extreme, the lives of Bobby Sands and Raymond Lohan are starkly juxtaposed against each other with both following the orders of their respective leaders but both deeply unhappy and resentful of their predicaments. Fassbender and Graham deserve immense credit for their magnificent yet tortured performances and six years hence Graham has continued to work in a multitude of Irish films as well as starring in Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy in 2011 whilst Michael Fassbender has rightly soared into the Hollywood stratosphere with career defining roles in Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Bastards, re-teaming with Director McQueen in the fantastic Shame and 12 Years a Slave as well as Ridley Scott’s Prometheus.

With so few characters and indeed very little dialogue, further supporting roles of note fall to Helen Madden as Bobby’s Mother “Mrs Sands” and Des McAleer as his Father “Mr Sands” and a heart breaking wordless performance from B J Hogg as “Loyalist Orderly”, but the stand out supporting role comes from the wonderful Liam Cunningham in his role as “Father Dominic Moran”. The Republican Father and Bobby share a seventeen minute, one camera, eponymous scene that will surely in the fullness of time come to be regarded as one of the greatest single dramatic scenes in cinema history. One camera, dialogue heavy and two actors putting in iconic performances that are so separate from the film’s grim reality yet complimenting it perfectly too. I hope I do this scene a modicum of justice with the following brief appraisal:

The scene opens with Bobby sitting alone at the table, naked apart from prison issue trousers. Off camera, Father Dominic enters the room and they exchange pleasantries which continue after the Father joins him at the table and they share the Father’s cigarettes. Both men are smiling and clearly pleased to see each other and to be having a human and refreshing conversation. Bobby dominates the conversation yet clearly wishes to hear the Father’s recent exploits in the outside world and of his family and background in Northern Ireland. The Father is still pursuing the “business of the soul” which amuses them both as they share his cigarettes and The Father retorts it’s “better than smoking the bible!” The Father questions Bobby as to why he called the meeting. Bobby is reluctant at first to discuss this and also brushes away the questions of who gave him his facial bruises and who beat him. They both discuss talk of negotiations and the orders from the upper levels of the IRA leadership.

Throughout their light hearted discussions so far both men have been self effacing and able to ridicule their religion and the bible, but as the Father presses Bobby more he becomes more and more indignant at the futility of the negotiations and the constant lack of real progress. “We’re starting a hunger strike on 1st March. That’s why you’re here. That’s what I’m telling you”. His tone is rising to which The Father replies that he’s a “Leader of Men” and he questions where Bobby gets his vast energy from. The tension breaks as Bobby half smiles and confirms he was a cross country runner as a boy before reiterating his frustrations again and despite the first hunger strike failing this time it will be different. 75 committed men will take part, each starting two weeks apart. The Father shows his first sign of anger at Bobby’s statement and at the impact this will have on the other men’s families and angrily asks him “why should you care as you’re dead, right?”. Bobby replies indignantly again that negotiations have failed and they need to act like soldiers in a war who are prepared to die for their cause.

The Father’s anger is growing yet he calmly chides Bobby that being locked up 24/7 is impairing his decision, he can’t think straight and he can’t put the lives of the men at risk in this way. He may be a freedom fighter but he’s needed in the outside world, working and negotiating for the cause as he did before. He beseeches Bobby to stop the planned action but he refuses, accusing The Father of simply seeing the issue as a matter of theology and not and of using as a tool against him. The Father, his voice rising in anger now accuses Bobby of using him as a sounding board for his ideas, with Bobby retorting with a half smile and in a mocking fashion “Aye, business of the soul”. For the first time in the entire seventeen minute scene the camera changes angle, a close up of Bobby taking another of The Father’s cigarettes and as he light’s the cigarette the camera pans in to a close up of Bobby as he relaxes and shares the story of his cross country running in Derry as a 12 year old boy he alluded to earlier. After concluding the story, he fixes The Father with a final stare.

“I’m clear on the reasons, Dom. I’m clear of all the repercussions. But I will act, and I will not stand by and do nothing”.

Despite the subject matter and being an especially difficult watch, Hunger should be lauded as an incredible debut achievement from Steve McQueen. With minimal dialogue he allows the roaming camera to tell his story for him and of course three remarkable character portrayals from Fassbender, Graham and Cunningham. McQueen also cleverly uses stock radio and TV interviews of the day, unseen and in the background as a semi narration, with an especially poignant use of an address to The Houses of Parliament by Margaret Thatcher. There is also clever use of a minimal musical score which sounds like a fiddle, mournful and foreboding and eerily reminiscent of a prison bell tolling in the background as it builds further tension, adding further layers to a remarkable film and the telling of a story that to this day remains a dark stain on the British psyche.

A phenomenal film.

Thanks for reading. Just for larks as always, and always a human reaction rather than spoilers galore. My three most recently published film articles are linked below or there’s well over 100 blog articles (with 300+ individual film reviews) within my archives from which to choose:

“Adaptation” (2002)

The surreal inner workings of Charlie Kaufman.medium.com

“Se7en” (1995)

The Best of David Fincher — Vol 2.medium.com

“You Were Never Really Here” (2017)

“It is a beautiful day”.medium.com