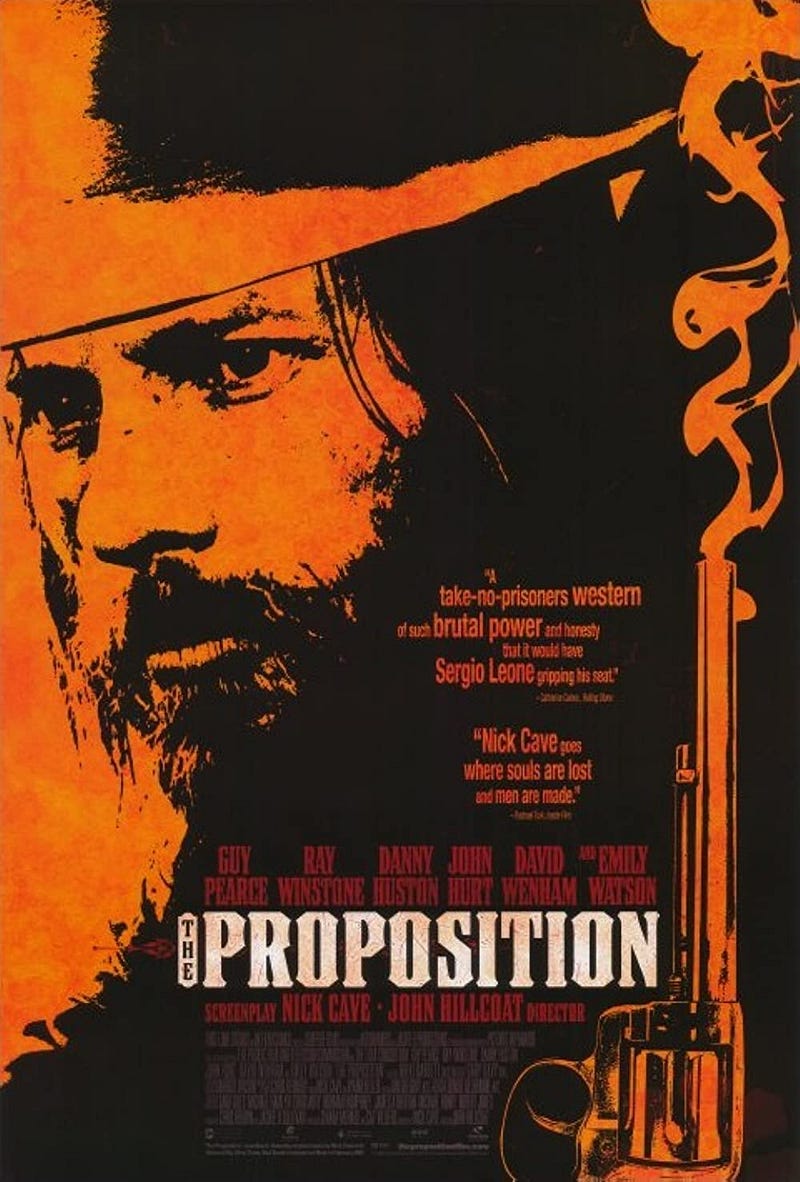

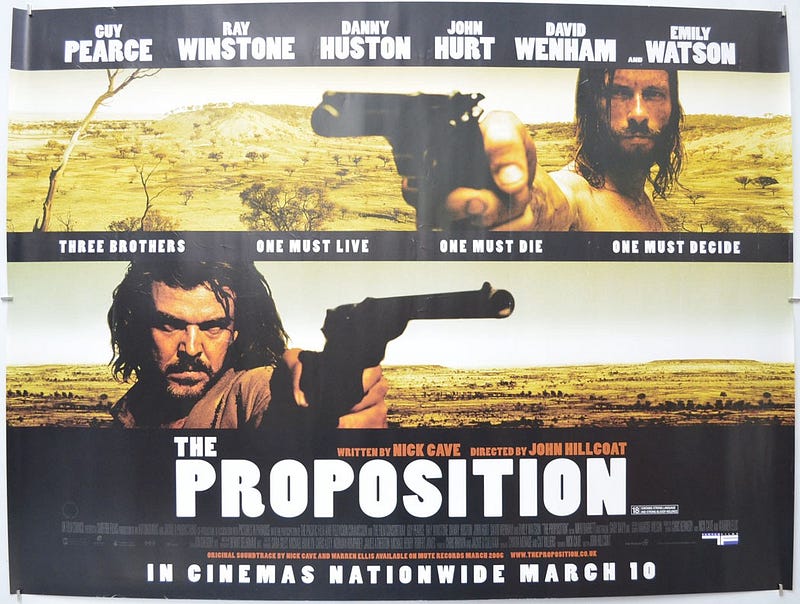

“The Proposition” (2005)

“Australia — What fresh hell is this?”

“Australia — What fresh hell is this?”

At the time of writing, a cold but bright English afternoon on the eve of Christmas Day 2022, director John Hillcoat has added two further cinematic releases not covered within a career catalogue I originally penned in 2013 before updating in 2016, and which is linked at the bottom of this brief opening salvo. Since this time he’s released a short film entitled Corazon as well as a documentary film on the life of Bob Dylan in 2021.

I cover the first five films in the cinematic career of John Hillcoat in the blog article below and from which I’m re-producing only one in full as unsurprisingly, The Proposition is my favourite and arguably a modern day classic. I’d also argue his “run” of films, from The Proposition here through the heart break of The Road and onto Lawless, 2005–2012, is a mighty fine run indeed. I may well re-release my musings on The Road. Incredible film. It just destroys me. It’s a father/son thing!

Anyway, my near decade old musings on John Hillcoat’s finest directing achievement.

John Hillcoat — Life through his Lens

“Ghosts of the Civil Dead”, “The Proposition”, “The Road”, “Lawless” and “Triple 9”. 1988 through 2016. Spoiler free!medium.com

“Australia — What fresh hell is this?”

With simple opening credits interspersed with Black and White pictures of an Australia of the 1880’s and concentrating on the plight of the native aborigines, we break from the quiet opening and are immediately transported into a violent and bloody shootout and the introduction to three of our main characters, “Charlie Burns”, his brother “Mike Burns” and Police Captain “Morris Stanley”. The Burns brothers are wanted for an unseen gruesome killing and rape and Captain Stanley has a proposition for Charlie — Kill his older brother Arthur and he and his younger brother Mike will be pardoned.

With at times minimal dialogue, but a tremendous and tight screenplay by Nick Cave, Nick also provides another delight in this film, the haunting and beautiful soundtrack with violinist Warren Ellis. This is also at times minimalist, but to great effect and accompanies the film perfectly. As does a whispering, barely audible narration. A special mention is also due to Director of Photography Benoit Delhomme, as with John Hillcoat’s direction, the Australian outback is perfectly shot. Lingering shots of the wide open, dirty and dusty outback set the tone, as does the frequent use of long distance shots of a sun setting on a barren, remote part of a barely inhabited world. There are numerous iconic shots of brilliantly framed setting sun’s, of Arthur Burns sitting atop his mountain retreat and especially of brothers Arthur and Charlie sitting on the same mountain peak, with a setting sun between them.

“Charlie Burns” (Guy Pearce) Brilliant as the quiet, melancholic and thoughtful Burns Brother. Minimal dialogue yet with the camera constantly focussing on Charlie, this is a nuanced and still performance from Pearce.

The centre and heart of the film with all the ensuing madness surrounding him.

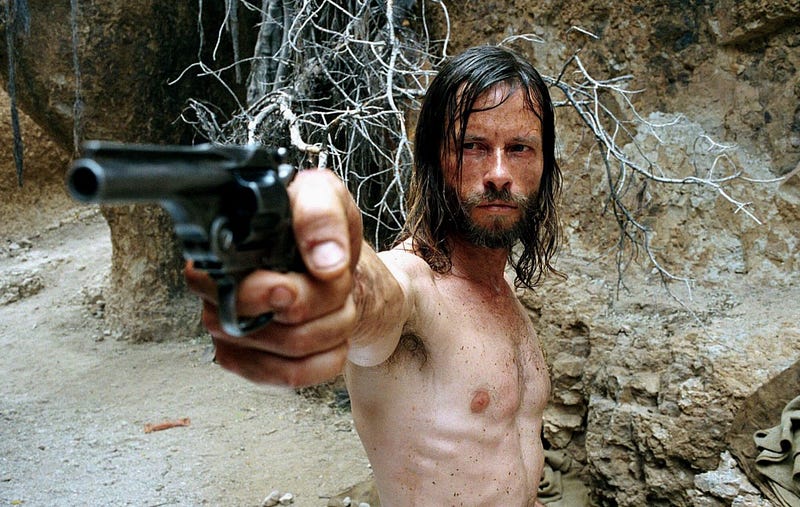

“Arthur Burns” (Danny Huston) The oldest of the Burns Brothers and the acting familial Patriarch. A roaring performance of violence and intensity and near career best from Huston despite being absent from the film until well into Act Two.

A brilliant performance.

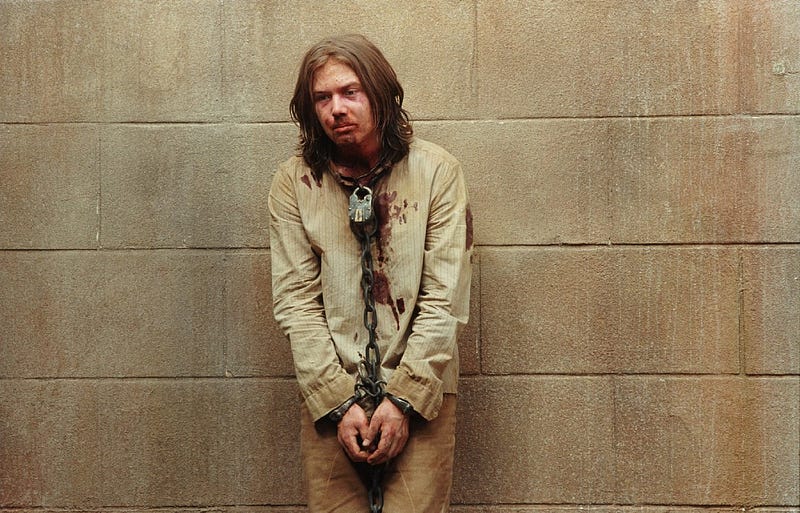

“Mike Burns” (Richard Wilson) Imprisoned and held as bait for his older Brothers, an adept performance from Wilson as the backward and scared Brother.

In pursuit of the Burns Brothers, and heading up the supporting roles is a brilliant portrayal from Ray Winstone as “Captain Stanley” and Winstone brings this archetypal Englishman to life with yet another captivating performance. Eloquent and forceful, yet brooding with a simmering nervousness, we follow his descent as he disintegrates before our eyes. It’s a powerful performance and yet mainly with his eyes, as although eloquent he seems unable to fix his stare to anyone except his wife. His eyes are forever darting left and right, anywhere but to the person speaking. Deeply in love with his wife “Martha Stanley” (Emily Watson), they seem determined to live a very English life amid the barren emptiness that surrounds them. It’s interesting to note throughout the film how the colour and texture changes from scene to scene and it’s especially evident when surrounding Captain Stanley and Martha. From the yellow stained and saturated colour of the Australian outback and it’s settlers, to that of full bright colours shown when with Captain Stanley, or at his home.

All main characters are richly detailed and layered with brilliant portrayals notably “Jellon Lamb” (John Hurt) who in a stunning cameo appearance stands out. Just two scenes and minor screen time but a joy, especially the bar room discussion with Charlie Burns and their abstract discussion on Charles Darwin and the Origin of the Species. A telling, well played scene. “Brian O’Leary” sees Noah Taylor make the first of his two cameo appearances for the Director in his films and “Jacko” is brilliantly played by David Gulpili, however the stand out cameo supporting role falls to David Wenham as “Eden Fletcher”.

A portrayal of late nineteenth century Australia and it’s appalling treatment of the indigenous tribes of aborigines it most certainly is. But deeper than that, a film of loyalty, friendship and family. There are also many juxtapositions throughout the film that are key, showing a light and dark of the situation, of the human condition even, that pervaded at the time. Many beautifully shot sunrises against the daily setting sun and the countdown to Mike’s execution. Captain Stanley’s twice quoted “I will civilise this land”, cut directly against the poor treatment of a juvenile Mike in prison is a stark juxtaposition, as is the poignant split scene of a singing gang member miles away and oblivious to the flogging being meted out to Mike. There’s a high sense of racism throughout the film, yet an Aborigine works under the command of Captain Stanley and his police. Similarly, another Aborigine works at the Captain’s plush home, which is set against the poor conditions within the town. A killing spree by the Police is juxtaposed with a drunken rendition of “Rule Britannia”. All these juxtapositions and many more are soaked throughout the film, as is the constant question, the proposition, at the beginning of the film — Will you kill your own brother to save the life of another brother? To describe the film as slow and melancholic (at times) would seem to be a criticism, but it isn’t. It fits the film and the story it tells perfectly. The violence is fleeting and you often only see the aftermath of the violence without the graphic portrayal, one scene is the exception to this and is heartbreakingly brutal.

A wonderful film, and the reason why I immediately became a John Hillcoat fan, eagerly awaiting the Director’s next release.

Thanks for reading. Just for larks as always, and always a human reaction rather than spoilers galore. My three most recently published film and television articles are linked below or there’s well over 100 blog articles (with 300+ individual film reviews) within my archives from which to choose:

LINK!

LINK!

LINK!